Time

28 May - 4 July 2010

curated by Chiara Williams & Debra Wilson

curated by Chiara Williams & Debra Wilson

articipating Artists

Anthea Henderson

Boa Swindler

Caroline Walker

Chantal Powell

Chiara Williams

Flora Parrott

H. Williams

Ingrid Berthon-Moine

Jarik jongman

Jayne Wilton

Liane Lang

Liesel Böckl

Lorraine Clarke

Momoko Suzuki

Phil Illingworth

Rob Miller

Stephanie Wehowski

Anthea Henderson

Boa Swindler

Caroline Walker

Chantal Powell

Chiara Williams

Flora Parrott

H. Williams

Ingrid Berthon-Moine

Jarik jongman

Jayne Wilton

Liane Lang

Liesel Böckl

Lorraine Clarke

Momoko Suzuki

Phil Illingworth

Rob Miller

Stephanie Wehowski

Text by Sophie Dodds

Time is a big a topic and I am certainly not Stephen Hawkins, so when the curators of the WW gallery asked me to write an essay for their exhibition about Time, I decided to go to Greenwich, the self-declared 'Home of Time and Longitude', to give myself a starting to point - an intellectual meridian line, so to speak. In the Time Gallery at Greenwich I realised that when I think about 'Time' I think about a very specific aesthetic - dry, well-proportioned, spindly, elegance - typified by Harrison's four time-pieces with their baroque scrolls engraved amongst gleaming cogs. But this aesthetic, as with the whole world of standardised, mechanised time-keeping, is the respectable face of a very messy topic.For time, as Einstein pointed out, is relative and we each experience it in a different way. If you say the word 'time' to a lot of people, they will think not about clocks and mechanics but about their own lives and what chances are left to them as their allotted period slides swiftly into the past. God knows what David Bowie meant when he sang, 'Time, he flexes like a whore, falls wanking to the floor', but I get the feeling he was approaching the topic with the kind of dark humour necessary to stay sane. With a similar playfulness, this exhibition is teasing apart the word 'time', each work coming at it from a different angle. Anthea Henderson's 'Snark' is a good starting point as it stands on the line between the mechanical and the emotional sense of the word; a standardised time-piece marking the passing minutes, decorated with shells and other found objects collected from seaside town souvenir shops. Despite the cuckoo programmed to spring out on the hour, this clock will never announce the present moment but only remind us, with an air of forlorn nostalgia, of the forgotten, the tacky and the out-of-date.

Liane Lang's film 'Ticker' also draws on the tension between the time that is marked by clocks and the passing of the sun and the time that the mind understands. A little less humorous than Henderson's clock in its approach, the solitary figure in the film swaddles themselves in wilful ignorance against the passing hours. Whilst the film's frenetic soundtrack plays out, we are only reassured that the figure is not dead by the occasional twitching movement. It brings to mind Walter Benjamin's description of boredom as "a warm gray fabric lined on the inside with the most lustrous and colourful of silks" whose wonder we cannot share with others, "for who would be able at one stroke to turn the lining of time to the outside?" (The Arcades Project)

Liane Lang's film 'Ticker' also draws on the tension between the time that is marked by clocks and the passing of the sun and the time that the mind understands. A little less humorous than Henderson's clock in its approach, the solitary figure in the film swaddles themselves in wilful ignorance against the passing hours. Whilst the film's frenetic soundtrack plays out, we are only reassured that the figure is not dead by the occasional twitching movement. It brings to mind Walter Benjamin's description of boredom as "a warm gray fabric lined on the inside with the most lustrous and colourful of silks" whose wonder we cannot share with others, "for who would be able at one stroke to turn the lining of time to the outside?" (The Arcades Project)

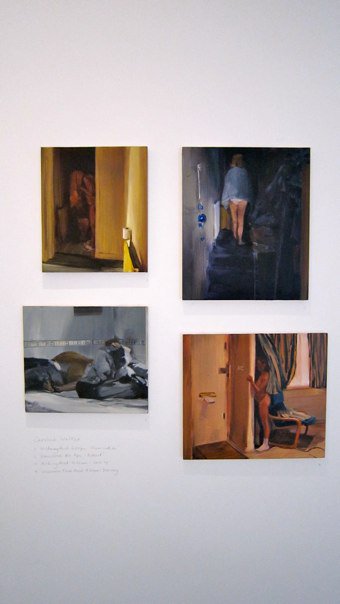

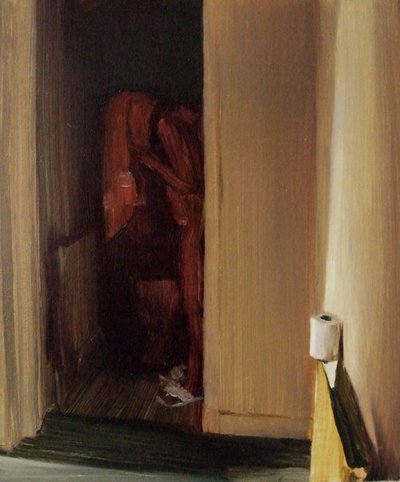

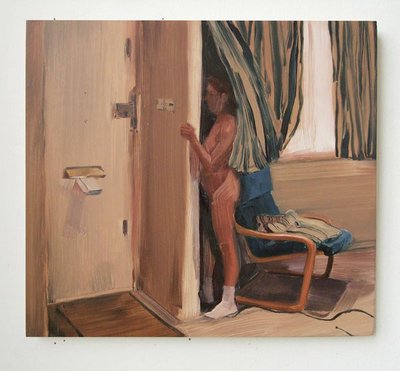

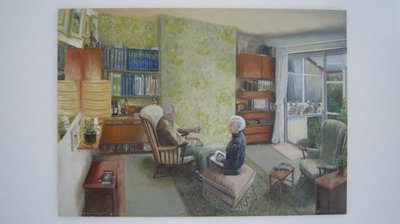

Caroline Walker 's paintings also use the domestic setting to offer a glimpse into this world of personal, internal time. They have a soft uneasiness about them, created perhaps by the contrast between the medium of paint, which is slow and methodical, and the fact that none of these scenes are stationary moments - the sun slides across the wall in 'Mildmay Park 6.20pm: Illumination' , the letter falls through the letter box in 'Gloucester Place 7.30am: Delivery' and the subject moves through the space or struggles with towels or duvets. They are obviously snapshots but their stillness and sensitivity to depth and light recall less of photography than 17th c. Dutch painting. The titles of the paintings tell the time but I get the sense that the figures are entirely unaware of it, lost in the timeless space of thought.

Another thing I hadn't really considered until visiting the Time Gallery was the difference between standardised time and local time, and the psychological implications of this for the individual. In the age before mechanised clocks, people would rely on sundials, and a sundial will always tell a specifically localised time - ie. a sundial in Norwich will tell noon 5 minutes before a sundial in London. Now the requirements of globalised commerce have committed us all to standardised time, where 'master' clocks are connected to 'slave' clocks in transport systems, media centres and other public spaces. Walker's paintings, for me, represent the contrast between localised or 'individual' time and standardised 'collective' time and evoke that feeling of relaxation that comes only when you stop thinking about what time it is for the rest of the world.

It is important to remember how our relationship with time has evolved throughout history. Few things have spelled this change out to me more clearly than a clock on display in 'Gladstone's Land', a house in Edinburgh's old town refitted to look exactly like that of a 17th. merchant. This clock did not have a minute hand, which was, apparently, a commonplace omission in an age where calculating things to the nearest minute was rarely a necessity. Phil Illingworth's 'Message to a Previous Self (Time Machine)' is also a device from a pre-digital era, at odds with the classic 'Time' aesthetic of Greenwich. This is not an infinitely complex, whirring mechanism, such as that described by H. G. Wells in 'The Time Machine', but an endearing little wooden talisman made of 150 year old oak. Hidden inside one of the 'controls' is a drawing, which Illingworth would send back to his younger self to help him along the way. Perhaps with this wonky machine, lllingworth is gently mocking the pointlessness of the older generation's persistent desire to impart their wisdom to the young.

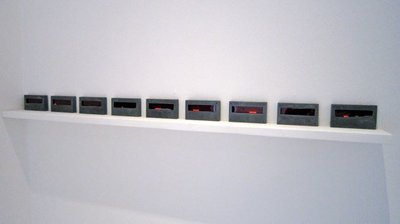

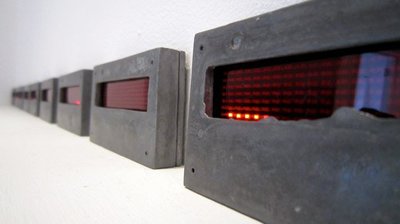

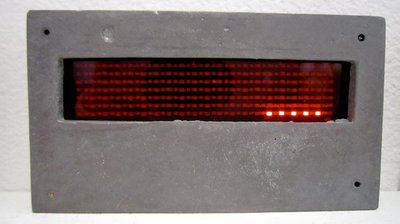

If Illingworth's piece is from a pre-technological age, Rob Miller's ‘Colon', ‘Underscore' and ‘Cursor' are, by contrast, bang-up-to-date time-pieces of the 21st century. It is a given, of course, that we now live in a time-obsessed society (atomic clocks can now tell time to an accuracy of 10 to the power of -9 seconds a day). Miller's works, taking their cue from departure boards, hospital waiting areas, motorway signs or supermarket checkouts, remind us, in anxious red characters, of the scarcity of that most precious of commodities and of the terror and panic instilled by the word 'time'. Moreover, they remind us succinctly of the fact that worrying about time is one of the most sure-fire ways of wasting it.

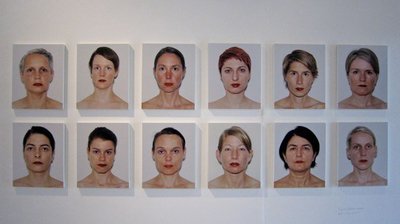

I often wonder what would happen if the world suddenly stopped looking at clocks and reverted to allowing the sun and our own biological instinct to tell the time. We surely don't give our bodies enough credit; how many of us, for example, seem to wake everyday just a few minutes before the alarm goes off? Women, of course, are often talked about as having inbuilt 'body clocks', body clocks that mysteriously synchronise when they live together and which are allegedly connected to the lunar cycle. This natural time-keeping is undoubtedly one of the contributing factors to the idea of uncanny, feminine power. Ingrid Berthon-Moine explores this in her highly unsettling 'Red is the Colour'. Here are twelve women, each wearing their own menstrual blood as lipstick, each of whose bodies knows, more or less, what time of the month it is, each of whom has an unknown time frame to harness their feminine wiles and get pregnant, if that is what they want. I've often thought that women and men have a very different concept of time and, if anything, that it is their tendency to plot and plan, to 'oversee' time that gives women their supposed 'power'.

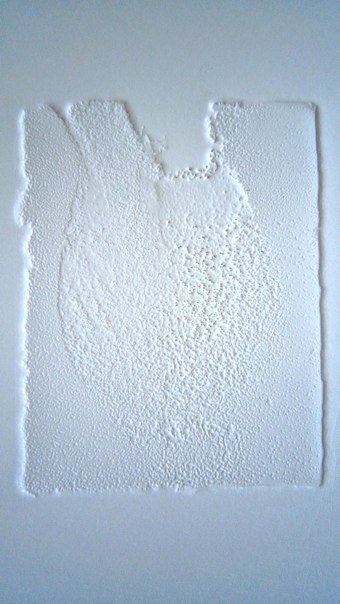

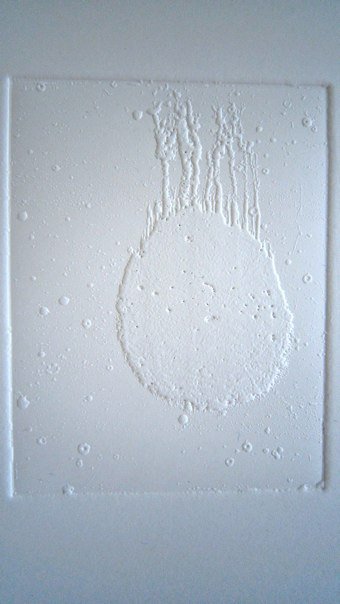

Jayne Wilton's 'Breathe' and ‘Relief' also deals with deposits and bodily cycles although this time in a more gender neutral way. By creating copper-plate etchings from the condensation left from a single breath, Wilton has discovered a way to catalogue the most ephemeral of human actions. The different patterns left by different breathers speak touchingly of our individuality but also of the fragility of that identity. Although, in a sense, the breathers have 'immortalised' themselves on these plates, even they have begun their own ageing-process as they begin to oxidise and change colour.

Another thing I hadn't really considered until visiting the Time Gallery was the difference between standardised time and local time, and the psychological implications of this for the individual. In the age before mechanised clocks, people would rely on sundials, and a sundial will always tell a specifically localised time - ie. a sundial in Norwich will tell noon 5 minutes before a sundial in London. Now the requirements of globalised commerce have committed us all to standardised time, where 'master' clocks are connected to 'slave' clocks in transport systems, media centres and other public spaces. Walker's paintings, for me, represent the contrast between localised or 'individual' time and standardised 'collective' time and evoke that feeling of relaxation that comes only when you stop thinking about what time it is for the rest of the world.

It is important to remember how our relationship with time has evolved throughout history. Few things have spelled this change out to me more clearly than a clock on display in 'Gladstone's Land', a house in Edinburgh's old town refitted to look exactly like that of a 17th. merchant. This clock did not have a minute hand, which was, apparently, a commonplace omission in an age where calculating things to the nearest minute was rarely a necessity. Phil Illingworth's 'Message to a Previous Self (Time Machine)' is also a device from a pre-digital era, at odds with the classic 'Time' aesthetic of Greenwich. This is not an infinitely complex, whirring mechanism, such as that described by H. G. Wells in 'The Time Machine', but an endearing little wooden talisman made of 150 year old oak. Hidden inside one of the 'controls' is a drawing, which Illingworth would send back to his younger self to help him along the way. Perhaps with this wonky machine, lllingworth is gently mocking the pointlessness of the older generation's persistent desire to impart their wisdom to the young.

If Illingworth's piece is from a pre-technological age, Rob Miller's ‘Colon', ‘Underscore' and ‘Cursor' are, by contrast, bang-up-to-date time-pieces of the 21st century. It is a given, of course, that we now live in a time-obsessed society (atomic clocks can now tell time to an accuracy of 10 to the power of -9 seconds a day). Miller's works, taking their cue from departure boards, hospital waiting areas, motorway signs or supermarket checkouts, remind us, in anxious red characters, of the scarcity of that most precious of commodities and of the terror and panic instilled by the word 'time'. Moreover, they remind us succinctly of the fact that worrying about time is one of the most sure-fire ways of wasting it.

I often wonder what would happen if the world suddenly stopped looking at clocks and reverted to allowing the sun and our own biological instinct to tell the time. We surely don't give our bodies enough credit; how many of us, for example, seem to wake everyday just a few minutes before the alarm goes off? Women, of course, are often talked about as having inbuilt 'body clocks', body clocks that mysteriously synchronise when they live together and which are allegedly connected to the lunar cycle. This natural time-keeping is undoubtedly one of the contributing factors to the idea of uncanny, feminine power. Ingrid Berthon-Moine explores this in her highly unsettling 'Red is the Colour'. Here are twelve women, each wearing their own menstrual blood as lipstick, each of whose bodies knows, more or less, what time of the month it is, each of whom has an unknown time frame to harness their feminine wiles and get pregnant, if that is what they want. I've often thought that women and men have a very different concept of time and, if anything, that it is their tendency to plot and plan, to 'oversee' time that gives women their supposed 'power'.

Jayne Wilton's 'Breathe' and ‘Relief' also deals with deposits and bodily cycles although this time in a more gender neutral way. By creating copper-plate etchings from the condensation left from a single breath, Wilton has discovered a way to catalogue the most ephemeral of human actions. The different patterns left by different breathers speak touchingly of our individuality but also of the fragility of that identity. Although, in a sense, the breathers have 'immortalised' themselves on these plates, even they have begun their own ageing-process as they begin to oxidise and change colour.

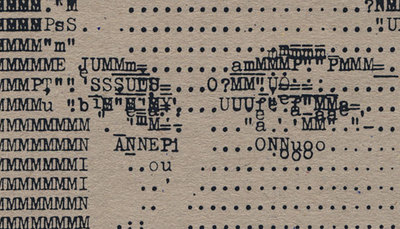

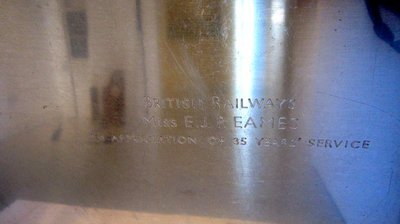

Time is ultimately the most precious commodity we have and one of the greatest gifts we can give someone is our own time (particularly in a place like London). Yet few of us are capable of distributing our time in the way we would like and we try, in particular, not to think too much about the time claimed by work. Boa Swindler's found items in 'Job for Life' acknowledge this with solemn humour; a lacklustre tray and a drab mantelpiece clock - bearing inscriptions that commemorate years of dedicated service - become anti-monuments in the face of their recipient's sacrifice. For these reasons, the value of Momoko Suzuki's ‘Untitled Drawing Project: Portrait series, Night' should be gauged not in terms of the skill involved or the appearance of the finalised piece, but the time she has allocated to the gallery during her residency there, in order to make the drawing. Each part of the drawing will be a deposit, building up like rock formations, of the time she has spent there.

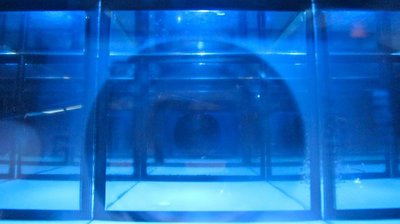

Finally, whilst the word 'time' elicits a negative reaction in many people, it's important to remember that it is not an unforgiving master. It is - at the end of the day, so to speak - the 'great healer' and over time we are capable of weaving the seemingly senseless events of our lives into a sort of narrative. Jarik Jongman's 'Swimming Pool 2' has that feeling of resolution about it. The swimming pool, seen in the dying light of day, has been long deserted and subject to decay, but has gained in these processes a more profound beauty.

Other artists in TIME:

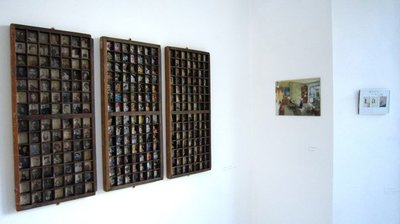

Chantal Powell's ‘Someone To Watch Over You' ( Triptych) speaks of our anonymity and temporality as individuals within the context of time. Images and deeds may be recorded but the recollection of identity is subject to change, manipulation, it is as vulnerable as our own personal memories. Time is relentless – it precedes us and will outlast our existence.

Flora Parrott's ‘Inhale, Hold it' uses black electrical tape, gaffer tape, bone, copper nails, copper pipe, wood, black thread and photographic prints of inflated cheeks to create an installation that is a kind of 3D diagram of the rhythm and tensions of breathing and the opposing impulses of breathing (in and out) and holding breath. Tensions arise between release and suffocation, which lead you to think more closely about the fragility and preciousness of life.

H. Williams' charming painting ‘Twilight' is a portrait of himself and his wife Marjorie in their sitting room in 1994. Ten years later Chiara Williams began a video portrait of Bill & Marjorie, her grandparents, in the same room. But with their health quickly deteriorating from cancer and Alzheimer's, she was only able to capture a few minutes of footage on the last day she spent with them both together. The footage lay untouched for several years and when recovered, she found it too had deteriorated. The resulting film ‘Twilight II' is a montage of a couple of hours spent with them as the light of day fades to evening; a patchwork of singing, laughing, crying, lost sound, dropped frames and empty spaces.

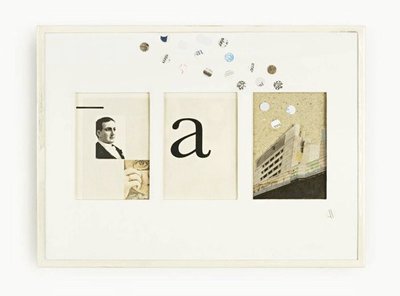

Liesel Böckl's mixed media collages ‘Into the Night', ‘Tempo Tempo' and ‘Victoria' are compositions that the artist describes as visual poems recording memories, thoughts and moments; they may derive from particular times in her life, but she hopes they will evoke a certain feeling or mood that will resonate with every new viewer.

Lorraine Clarke's ‘Change' combines the aneroid barometer - an instrument for determining atmospheric pressure, and chronic glaucoma - a condition in which the eye pressure rises very slowly (over many years) resulting in gradual loss of vision, this work is concerned with the consequence of lost time and how alterations in pressure bring about change.

Stephanie Wehowski's ‘The Fate of Modern Man?' is an enigmatic object that invites us to consider infinity, time and reflect on our purpose. Floating on the gallery wall, it recalls both a confessional booth and nun's veil, which we are invited to lift in order to peer in.

Finally, whilst the word 'time' elicits a negative reaction in many people, it's important to remember that it is not an unforgiving master. It is - at the end of the day, so to speak - the 'great healer' and over time we are capable of weaving the seemingly senseless events of our lives into a sort of narrative. Jarik Jongman's 'Swimming Pool 2' has that feeling of resolution about it. The swimming pool, seen in the dying light of day, has been long deserted and subject to decay, but has gained in these processes a more profound beauty.

Other artists in TIME:

Chantal Powell's ‘Someone To Watch Over You' ( Triptych) speaks of our anonymity and temporality as individuals within the context of time. Images and deeds may be recorded but the recollection of identity is subject to change, manipulation, it is as vulnerable as our own personal memories. Time is relentless – it precedes us and will outlast our existence.

Flora Parrott's ‘Inhale, Hold it' uses black electrical tape, gaffer tape, bone, copper nails, copper pipe, wood, black thread and photographic prints of inflated cheeks to create an installation that is a kind of 3D diagram of the rhythm and tensions of breathing and the opposing impulses of breathing (in and out) and holding breath. Tensions arise between release and suffocation, which lead you to think more closely about the fragility and preciousness of life.

H. Williams' charming painting ‘Twilight' is a portrait of himself and his wife Marjorie in their sitting room in 1994. Ten years later Chiara Williams began a video portrait of Bill & Marjorie, her grandparents, in the same room. But with their health quickly deteriorating from cancer and Alzheimer's, she was only able to capture a few minutes of footage on the last day she spent with them both together. The footage lay untouched for several years and when recovered, she found it too had deteriorated. The resulting film ‘Twilight II' is a montage of a couple of hours spent with them as the light of day fades to evening; a patchwork of singing, laughing, crying, lost sound, dropped frames and empty spaces.

Liesel Böckl's mixed media collages ‘Into the Night', ‘Tempo Tempo' and ‘Victoria' are compositions that the artist describes as visual poems recording memories, thoughts and moments; they may derive from particular times in her life, but she hopes they will evoke a certain feeling or mood that will resonate with every new viewer.

Lorraine Clarke's ‘Change' combines the aneroid barometer - an instrument for determining atmospheric pressure, and chronic glaucoma - a condition in which the eye pressure rises very slowly (over many years) resulting in gradual loss of vision, this work is concerned with the consequence of lost time and how alterations in pressure bring about change.

Stephanie Wehowski's ‘The Fate of Modern Man?' is an enigmatic object that invites us to consider infinity, time and reflect on our purpose. Floating on the gallery wall, it recalls both a confessional booth and nun's veil, which we are invited to lift in order to peer in.

Press Release

Time Time, he's waiting in the wings

He speaks of senseless things

His script is you and me, boy.

David Bowie

Time is by definition the measure used to sequence events. In this exhibition we see the artist as philosopher, scientist, historian and archaeologist. The artist marks, traces, passes, commemorates, measures, captures or defies time in one way or another, with works that confront and mediate life experiences, cycles and rites of passage. Narratives are used to examine and analyse sequences of events as a way of providing perspective on the problems of the present. For individuals, time holds economic value and reminds us of our own fragility and mortality and as it flows, time is at once the past, the present and the future. The 17 time-keepers and chroniclers in this exhibition explore the theme through sculpture, painting, video, photography, print, drawing, installation and time-based performance.

"there is an exhilaratingly deep range to take in", The Mirror, The Ticket

TIME is part of First Thursdays Guided Bus Tour July 1, 7–9pm

Further information about the artists:

Saint Martins graduate Momoko Suzuki will be in residence throughout TIME completing her ongoing time-based drawing installation, which fills an entire 12x10ft wall. Watch her drawing performance at the private view, First Thursdays and during gallery opening hours. Among the artists in TIME are LCC graduate Ingrid Berthon-Moine, whose series 'Red is The Colour' - c-type portraits of women wearing their menstrual blood as lipstick - caused controversy in the Guardian; RCA graduate Flora Parrott - whose work was reviewed in TimeOut as part of a concurrent show at Tintype gallery; former assistant of Anselm Kiefer, Jarik Jongman (reviewed in the Evening Standard last October), has been selected for the Threadneedle Prize and exhibits his sublime painting 'Swimming Pool 2'; also selected for the Threadneedle prize is award-winning Caroline Walker, who treats us to 4 paintings ahead of her two solo shows at Marlborough Fine Art, London and Ivan Gallery, Bucharest; Saatchi & Deutsche bank-collected Liane Lang presents her video ‘Ticker' ahead of her solo 'Shadows and Stowaways' at Squid & Tabernacle; Fresh Slade graduate and winner of the Foster Fletcher drawing prize, Jayne Wilton exhibits exquisite copper etching plates, many created during a recent Heal's residency, her work has been collected by Heal's archive, the Tate and UCL Slade; Phil Illingworth, who has just been selected for the John Moores Contemporary Painting prize, presents a time-machine made of 150 year old oak; Chantal Powell exhibits ‘Someone To Watch Over You' ahead of her solo show 'Traces and Testament'.

Time Time, he's waiting in the wings

He speaks of senseless things

His script is you and me, boy.

David Bowie

Time is by definition the measure used to sequence events. In this exhibition we see the artist as philosopher, scientist, historian and archaeologist. The artist marks, traces, passes, commemorates, measures, captures or defies time in one way or another, with works that confront and mediate life experiences, cycles and rites of passage. Narratives are used to examine and analyse sequences of events as a way of providing perspective on the problems of the present. For individuals, time holds economic value and reminds us of our own fragility and mortality and as it flows, time is at once the past, the present and the future. The 17 time-keepers and chroniclers in this exhibition explore the theme through sculpture, painting, video, photography, print, drawing, installation and time-based performance.

"there is an exhilaratingly deep range to take in", The Mirror, The Ticket

TIME is part of First Thursdays Guided Bus Tour July 1, 7–9pm

Further information about the artists:

Saint Martins graduate Momoko Suzuki will be in residence throughout TIME completing her ongoing time-based drawing installation, which fills an entire 12x10ft wall. Watch her drawing performance at the private view, First Thursdays and during gallery opening hours. Among the artists in TIME are LCC graduate Ingrid Berthon-Moine, whose series 'Red is The Colour' - c-type portraits of women wearing their menstrual blood as lipstick - caused controversy in the Guardian; RCA graduate Flora Parrott - whose work was reviewed in TimeOut as part of a concurrent show at Tintype gallery; former assistant of Anselm Kiefer, Jarik Jongman (reviewed in the Evening Standard last October), has been selected for the Threadneedle Prize and exhibits his sublime painting 'Swimming Pool 2'; also selected for the Threadneedle prize is award-winning Caroline Walker, who treats us to 4 paintings ahead of her two solo shows at Marlborough Fine Art, London and Ivan Gallery, Bucharest; Saatchi & Deutsche bank-collected Liane Lang presents her video ‘Ticker' ahead of her solo 'Shadows and Stowaways' at Squid & Tabernacle; Fresh Slade graduate and winner of the Foster Fletcher drawing prize, Jayne Wilton exhibits exquisite copper etching plates, many created during a recent Heal's residency, her work has been collected by Heal's archive, the Tate and UCL Slade; Phil Illingworth, who has just been selected for the John Moores Contemporary Painting prize, presents a time-machine made of 150 year old oak; Chantal Powell exhibits ‘Someone To Watch Over You' ahead of her solo show 'Traces and Testament'.