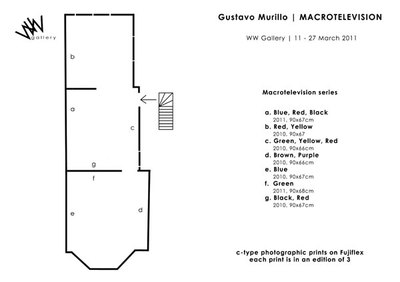

Gustavo Murillo | MACROTELEVISION

11 – 27 March 2011

curated by Chiara Williams and Debra Wilson

Press release

curated by Chiara Williams and Debra Wilson

Press release

| ww_gallery_gustavo_murrilopr.pdf | |

| File Size: | 153 kb |

| File Type: | |

WW Gallery is pleased to present ‘MACROTELEVISION' the first UK solo show for contemporary photographer Gustavo Murillo.

“Ultimately, Photography is subversive, not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.”*

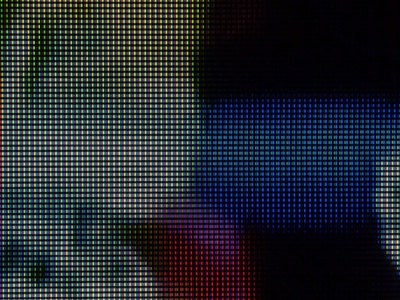

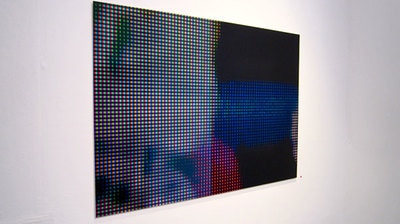

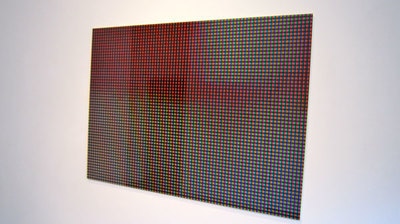

Murillo's abstract photographic series MacroTelevision is at once serene, seductive and reverent. These thoughtful and meditative works hypnotise the eye with their luminous colour, while reflecting the influence of television upon society.

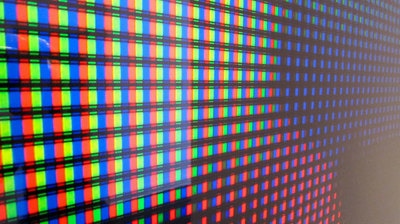

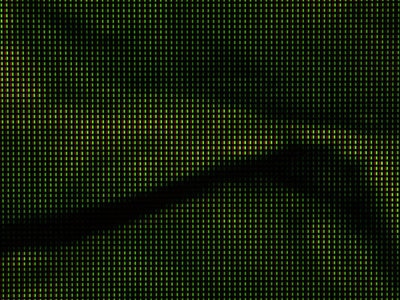

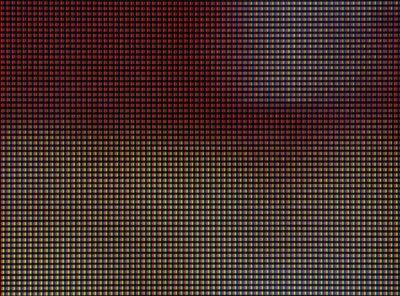

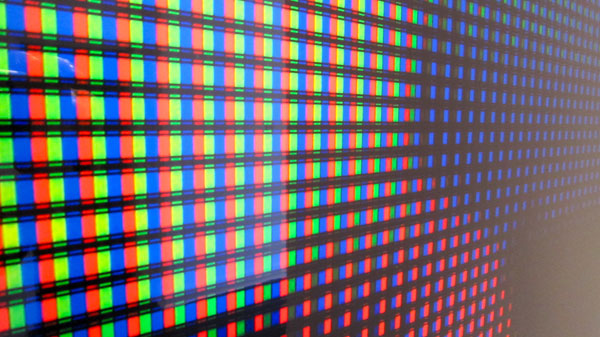

Murillo uses a sophisticated macro lens to frame a section of television screen, showing the lines of red, green and blue phosphor dots that make up the colour picture. The resulting photograph is a still image born of luminance, chrominance, and the synchronization of vertical and horizontal signals. More than a minimalist pattern, the abstracted image distances itself from the deciphered media message and is an antidote to television's tendency to induce cognitive overload.

From pointillism to pop and op, colour field painting and minimalism to self-referential concrete photography, Murillo's work operates formally and emotionally within the overlapping realms of contemporary modernist photography, painting and abstraction, dubbed by some as Remodernist.

----------

Gustavo Murillo (b. 1982, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain) graduated in Arts & Culture from the Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona. In January 2011, ‘Blue' from the MacroTelevision series, was shown with WW Gallery in Art Projects at the London Art Fair. MACROTELEVISION is Murillo's first UK solo show and the works will also be shown at Miscelanea Gallery, Barcelona in June 2011.

*(Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, London: Vintage, 2000, p 38.)

“Ultimately, Photography is subversive, not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.”*

Murillo's abstract photographic series MacroTelevision is at once serene, seductive and reverent. These thoughtful and meditative works hypnotise the eye with their luminous colour, while reflecting the influence of television upon society.

Murillo uses a sophisticated macro lens to frame a section of television screen, showing the lines of red, green and blue phosphor dots that make up the colour picture. The resulting photograph is a still image born of luminance, chrominance, and the synchronization of vertical and horizontal signals. More than a minimalist pattern, the abstracted image distances itself from the deciphered media message and is an antidote to television's tendency to induce cognitive overload.

From pointillism to pop and op, colour field painting and minimalism to self-referential concrete photography, Murillo's work operates formally and emotionally within the overlapping realms of contemporary modernist photography, painting and abstraction, dubbed by some as Remodernist.

----------

Gustavo Murillo (b. 1982, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain) graduated in Arts & Culture from the Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona. In January 2011, ‘Blue' from the MacroTelevision series, was shown with WW Gallery in Art Projects at the London Art Fair. MACROTELEVISION is Murillo's first UK solo show and the works will also be shown at Miscelanea Gallery, Barcelona in June 2011.

*(Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, London: Vintage, 2000, p 38.)

MACROTELEVISION

essay by Chiara Williams & Debra Wilson

“Ultimately, Photography is subversive, not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.”

(Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, London: Vintage, 2000, p 38.)

Murillo's abstract photographic series MacroTelevision is at once serene, seductive and reverent. These thoughtful and meditative works hypnotise the eye with their luminous colour, whilst operating in that grey and sometimes dubious area between art and photography and between photography and abstraction.

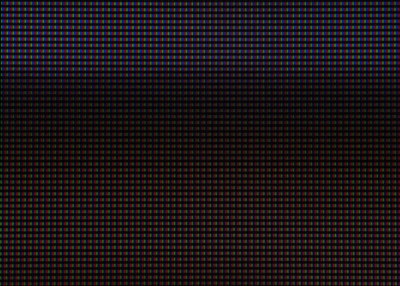

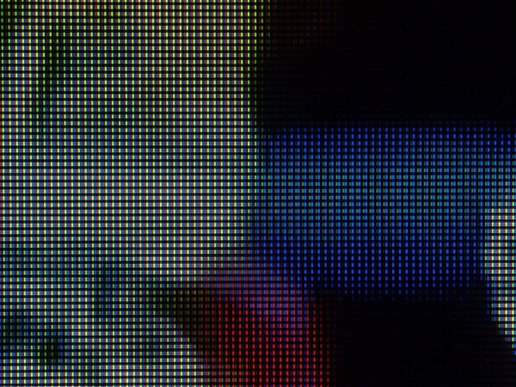

Murillo uses a sophisticated macro lens to frame a section of television screen, showing the lines of red, green and blue phosphor dots that make up the colour picture. Establishing the correct distance between lens and screen is key in bringing the RGB screen dots, and the spaces between them, closer to the viewer's eye and allowing the brain to fill in the missing pieces of information. Each dot and each space is a cipher of a larger meaning. The viewer can then choose whether to engage or disengage their selective attention. It is the discrepancy between the original signal transmission and the actual analogue reception, and all the inherent limitations of this mass medium, which inform Murillo's work and which is here amplified and magnified.

Murillo is interested in television's influence upon western society, the way in which it is watched religiously and has become part of our interior furnishings. To paraphrase from John Berger's Ways of Seeing, when a television signal enters a viewer's house, “it is surrounded by his wallpaper, his furniture, his mementos. It enters the atmosphere of his family. It becomes their talking-point. It lends its meaning to their meaning. At the same time it enters a million other houses and in each of them is seen in a different context.”

essay by Chiara Williams & Debra Wilson

“Ultimately, Photography is subversive, not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.”

(Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, London: Vintage, 2000, p 38.)

Murillo's abstract photographic series MacroTelevision is at once serene, seductive and reverent. These thoughtful and meditative works hypnotise the eye with their luminous colour, whilst operating in that grey and sometimes dubious area between art and photography and between photography and abstraction.

Murillo uses a sophisticated macro lens to frame a section of television screen, showing the lines of red, green and blue phosphor dots that make up the colour picture. Establishing the correct distance between lens and screen is key in bringing the RGB screen dots, and the spaces between them, closer to the viewer's eye and allowing the brain to fill in the missing pieces of information. Each dot and each space is a cipher of a larger meaning. The viewer can then choose whether to engage or disengage their selective attention. It is the discrepancy between the original signal transmission and the actual analogue reception, and all the inherent limitations of this mass medium, which inform Murillo's work and which is here amplified and magnified.

Murillo is interested in television's influence upon western society, the way in which it is watched religiously and has become part of our interior furnishings. To paraphrase from John Berger's Ways of Seeing, when a television signal enters a viewer's house, “it is surrounded by his wallpaper, his furniture, his mementos. It enters the atmosphere of his family. It becomes their talking-point. It lends its meaning to their meaning. At the same time it enters a million other houses and in each of them is seen in a different context.”

The television communicates information and entertainment, but it is also background noise, a moving picture, a dancing pattern, for some, it is even company. An illustration of this can be seen in the TV comedy series The Royle Family, in which the television screen is both central and incidental to the drama, both active and passive; it becomes a kind of two-way mirror between the lives of the characters and the viewers, and the screen also stands for camera, lens and eye.

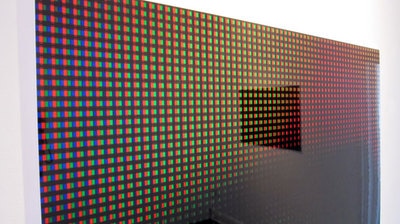

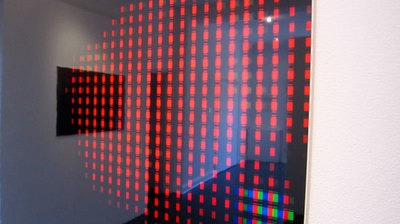

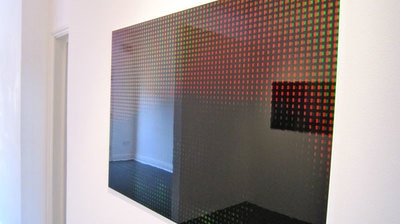

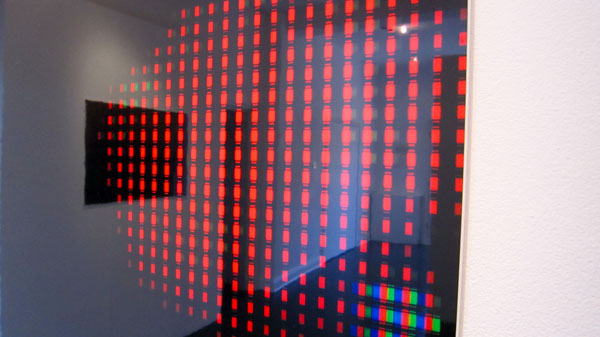

In making MacroTelevision, Murillo's lens forces the television screen toward the spectator, so that it becomes more than a passive televisual experience for the viewer. In addition, the scale of the photograph and its seductive high-gloss surface quietly reflects the image of the viewer back to himself, in the same way as a TV screen reflects you when you switch it off.

Murillo draws in the viewer through the emotional power of the colour in his work, a still image born of luminance, chrominance, and the synchronization of vertical and horizontal signals. More than a minimalist pattern, the abstracted image distances itself from the deciphered media message and is an antidote to television's tendency to induce cognitive overload.

Historically, photography and film became the visual paradigm of news and information, its success built upon the foundation of reflecting real things with immediacy, but a photographer looks through the lens of a camera critically, and he is always looking ‘at something'. The looking is active rather than passive, framing and abstracting from, and yet, he abstracts ciphers of the visible that he has at least once experienced in the phenomenal world, and he is recording, at least spiritually, the disintegration of its existence; its abstraction.

In general, the history of photographic aesthetics is identical with the history of modern art. The development of Abstract Painting has often been described as the inevitable consequence of the perfection and dominance of the 19 th century photograph, leading to painting for the sake of painting, modernism, abstraction. Photography, once it had tired of recording reality, inevitably followed suit.

Murillo's edited, spare and reductive photographs of TV signal dots inevitably relate to the science of vision and colour theory, and to the photographic traditions of Rodchenko, Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy, but they also resonate powerfully within the context of painting and the historical relationship between painting and photography: framing an imaginary section of Seurat's ‘La Grande Jatte', referencing Lichtenstein's ben-day dots, hinting at the shifting colours of simultaneous contrast on a Bridget Riley canvas, the saturation of Barnett Newman, the meditation of Rothko, the grids of Agnes Martin, the luminance of Flavin, the chrominance of Yves Klein, and most literally, to the videograms of René Mächler.

From pointillism to pop and op, colour field painting and minimalism to self-referential concrete photography, Murillo's work operates formally and emotionally within the overlapping realms of contemporary modernist photography, painting and abstraction, dubbed by some as Remodernist.

In making MacroTelevision, Murillo's lens forces the television screen toward the spectator, so that it becomes more than a passive televisual experience for the viewer. In addition, the scale of the photograph and its seductive high-gloss surface quietly reflects the image of the viewer back to himself, in the same way as a TV screen reflects you when you switch it off.

Murillo draws in the viewer through the emotional power of the colour in his work, a still image born of luminance, chrominance, and the synchronization of vertical and horizontal signals. More than a minimalist pattern, the abstracted image distances itself from the deciphered media message and is an antidote to television's tendency to induce cognitive overload.

Historically, photography and film became the visual paradigm of news and information, its success built upon the foundation of reflecting real things with immediacy, but a photographer looks through the lens of a camera critically, and he is always looking ‘at something'. The looking is active rather than passive, framing and abstracting from, and yet, he abstracts ciphers of the visible that he has at least once experienced in the phenomenal world, and he is recording, at least spiritually, the disintegration of its existence; its abstraction.

In general, the history of photographic aesthetics is identical with the history of modern art. The development of Abstract Painting has often been described as the inevitable consequence of the perfection and dominance of the 19 th century photograph, leading to painting for the sake of painting, modernism, abstraction. Photography, once it had tired of recording reality, inevitably followed suit.

Murillo's edited, spare and reductive photographs of TV signal dots inevitably relate to the science of vision and colour theory, and to the photographic traditions of Rodchenko, Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy, but they also resonate powerfully within the context of painting and the historical relationship between painting and photography: framing an imaginary section of Seurat's ‘La Grande Jatte', referencing Lichtenstein's ben-day dots, hinting at the shifting colours of simultaneous contrast on a Bridget Riley canvas, the saturation of Barnett Newman, the meditation of Rothko, the grids of Agnes Martin, the luminance of Flavin, the chrominance of Yves Klein, and most literally, to the videograms of René Mächler.

From pointillism to pop and op, colour field painting and minimalism to self-referential concrete photography, Murillo's work operates formally and emotionally within the overlapping realms of contemporary modernist photography, painting and abstraction, dubbed by some as Remodernist.